Film

Fashions in workplace design have changed since Office Space. When Mike Judge released his cult comedy of unhappy software programmers in 1999 – two years before Ricky Gervais launched The Office – his characters were still penned up in cubicles. The film flopped, but it would be nice to think that on some subliminal level it hastened the end of that particular era. Of course, what followed – hot-desks and the open-plan – was just as dreadful. But that much was in keeping with what Judge told us all along. A wilful printer can be destroyed. The rest of it? The pass-agg line manager? The presenteeism and paranoia? The hatefully chipper co-worker diagnosing a “case of the Mondays”? All that is eternal. You can’t change the office, Office Space said. You can only leave it. Danny Leigh

Books

View image in fullscreen Photograph: Vintage Classics

View image in fullscreen Photograph: Vintage Classics

Office culture is a contradiction in terms for Bob Slocum, the unhappy narrator of Something Happened by Joseph Heller. He endures long days of malevolence, melancholy and petty humiliation. His work shuts him off from the rest of the world. It drains him. If there is any kind of culture, it’s a culture of fear: fear of other colleagues, fear of being fired and fear of being stuck. So a pretty normal office, in other words. Heller’s follow-up to Catch-22 still resonates almost 50 years after it was first published in 1974. It is a book, as Kurt Vonnegut once said, “as clear and hard-edged as a cut diamond”. Sam Jordison

Games

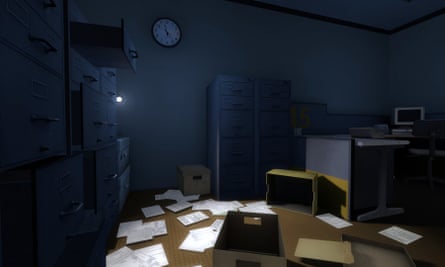

View image in fullscreenThe Stanley Parable. Photograph: Galactic Cafe

View image in fullscreenThe Stanley Parable. Photograph: Galactic Cafe

If, like any working human being on this planet, you have ever wondered what would happen if you just decided not to do what you’re told, you’ll relate to The Stanley Parable. Stanley’s job is to sit at a desk and press buttons on a computer in the order dictated to him by his boss. But one day no orders come – and when he leaves his little cubicle, things quickly turn brilliantly surreal. You can do what the narrator tells you, or play your own way in open defiance. An exuberant interrogation of the rules of both office life and video games. Keza MacDonald

Television

View image in fullscreenSophie Willan in Alma’s Not Normal. Photograph: Matt Squire/BBC/Expectation TV

View image in fullscreenSophie Willan in Alma’s Not Normal. Photograph: Matt Squire/BBC/Expectation TV

From the moment Alma Nuthall describes herself as “the baby from Trainspotting, if she’d lived”, you know Sophie Willan’s BBC sitcom Alma’s Not Normal isn’t going to mince words. Plenty of comedy has addressed white-collar drudgery, the ennui of office life. This goes darker, but with charm and nuance to burn. After a disastrous stint at a minimum-wage sandwich shop, Alma signs up with an escort agency. “Yes, I’m aware it’s sex,” she says bluntly during the phone interview. And the job isn’t agony and misery, nor is it some faux-decadent Belle de Jour fantasy. It’s sometimes OK, sometimes rubbish. In other words, it’s work. “Why do people always psychoanalyse sex workers?” Alma wonders. “Is Sue on the phones empowered?” It’s a fair question. Phil Harrison

Music

22 Grand Job by the Rakes.

A kind of Common People for millennials, the Rakes’ signature single, 22 Grand Job, led the way among an abundance of mid-00s bands who made a signature sound out of articulating their nine-to-five frustrations: Hard-Fi, the Enemy, the Ordinary Boys. Opening with a rattle of drums, its strident yet basic chant captures the frustration of relentless entry-level tedium, the heady thrill of your first full-time pay cheque butting heads with the recognition that this may indeed be your life for the next 50-plus years. Inflation has not been kind to its title, but the single’s core sensibility still feels alarmingly fit for 2021. Jenessa Williams